Themes in Max Frisch's work

Identity

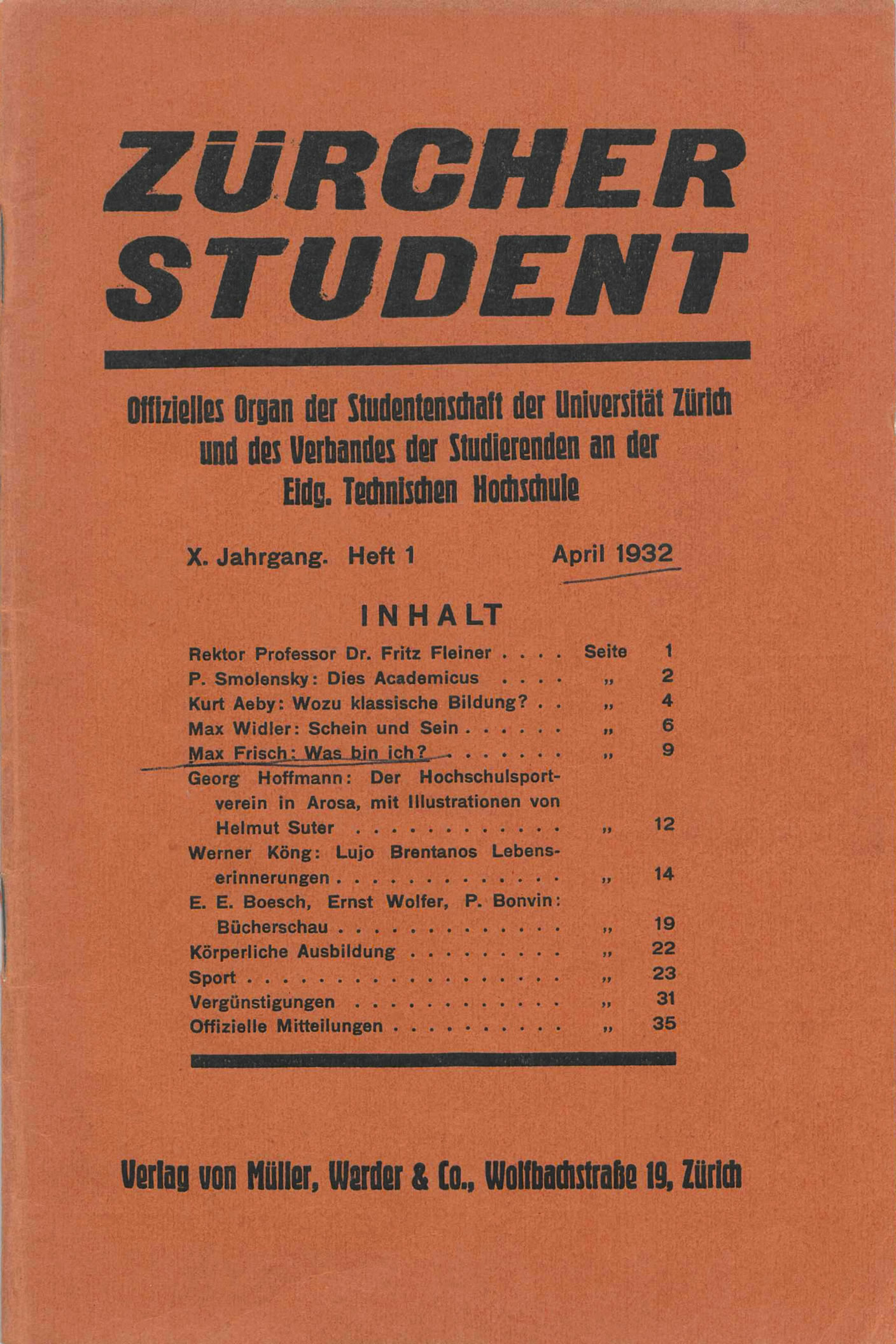

"Indeed, we have to begin with ourselves before we want to shape others", as the 23-year-old Max Frisch wrote in a text for "Zürcher Illustrierte". Frisch’s work centres around the notion of self. In the process, he does not overlook the objection to escapism. As he concedes in "Gantenbein": "I, too, often have the feeling that any book which is not concerned with the prevention of war, with the creation of a better society and so on, is senseless, futile, irresponsible, tedious, not worth reading, inadmissible. This is no time for ego stories." However, he then adds: "And yet human life is fulfilled or goes wrong in the individual ego, nowhere else."

Love and friendship

Max Frisch is famous for his questionnaires from "Tagebuch 1966–1971". Two out of five are devoted to personal relationships: one to marriage, the other to friendship. Ever since his youth, Frisch had desired bonds that do not come at the expense of vitality. "You shall not make for yourself any graven image," he wrote and took this biblical instruction as a model for a successful relationship: "Our belief that we know the other is the end of love." The author highlights the willingness "to undergo further transformations" and thus keep the secret that "after all, a human is an exciting puzzle that we've grown tired of tolerating".

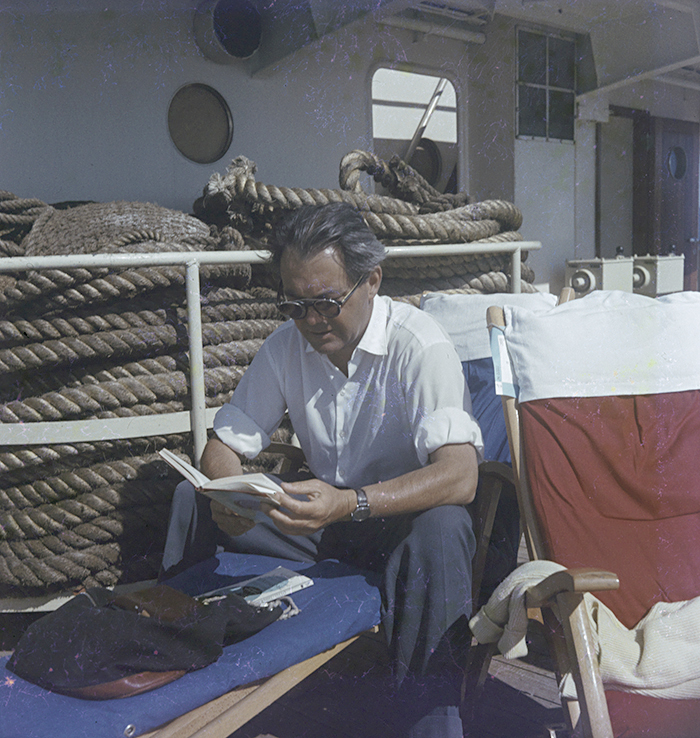

Travel

As the 24-year-old already noted in the wake of his first trip to Germany: "[A]s I saw myself incapable of earning a full living alongside a proper degree, I chose a different path: I travelled, as every Swiss man must if he is to avoid becoming a petty bourgeois," writes Frisch in a letter in 1936. He felt the need for new beginnings way beyond his degree. Turned into the transpersonal, it gave rise to the following acknowledgement in the first "Tagebuch": "How small our country is. / Our longing for the world, our desire for broad, flat horizons, […] our desire for water that connects us with all the shores of this Earth; our nostalgia for the foreign."

Architektur und Städtebau

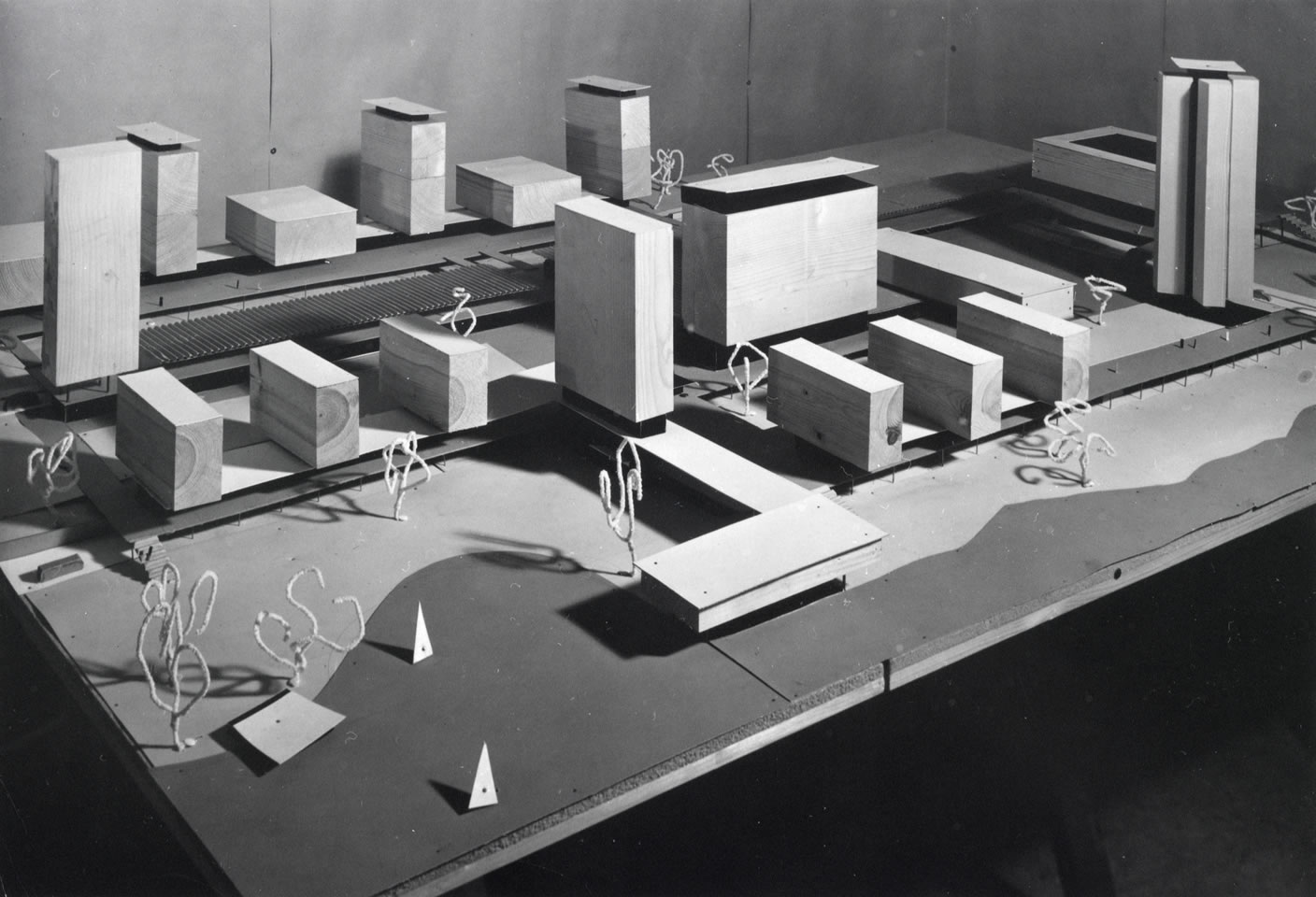

Architecture and urban design

"Why, of all things, an architect?" asks Frisch in his late book "Montauk" before providing the answer himself: "My father was an architect (without a diploma); the transparent tracing paper, the T-square that bobs up and down, the tape measure as forbidden toys. I draw more precisely than I have written thus far." Frisch only designed and realised a handful of buildings, including his famous Letzigraben outdoor pool in Zurich. All the same, reflections on architecture and urban design were also a key feature in his writing. His protagonist Anatol Stiller complains about Switzerland's despondency and the "nostalgia for the distant past". On the other hand, the proposal that Frisch put forward together with Lucius Burckhardt and Markus Kutter was extremely forward-looking: their design for a completely new city was discussed widely and external page continues to resonate to this day.

Technology

Frisch's characters include many engineers: his Don Juan loves women but geometry even more. Walter Faber explains bluntly: "I don’t believe in fate or providence; as a technologist, I'm used to calculating probability with formulae." Even an artist character like Stiller is imbued with an inclination towards craftsmanship. Now conciliatory, now admonitory, mankind's relationship with technology is a subject that Frisch examined throughout his life.

Politics

Frisch increasingly developed into a political citizen. Although he kept in touch with statesmen like Henry Kissinger, Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt, he followed current affairs from a critical distance. In "Tagebuch 1946–1949" he expresses the conviction that anyone who does not engage with politics is already taking political sides: "He is serving the ruling party." Despite his personal engagement, such as in support of the Group for a Switzerland without an Army (GSoA) or Italian migrant workers, he did not want his writing to serve politics: "The function of literature in society," said Frisch in his New York poetry lectures, "is the permanent irritation that it exists. Nothing more."